With the battle over federal furnace efficiency standards now before the Supreme Court, we’re joined by our utilities expert, Christopher Hailstone, to unpack the technical, legal, and practical implications of this landmark case. For years, Christopher has navigated the complex intersection of energy management, grid reliability, and regulatory policy, and today he’ll shed light on a debate that pits promises of consumer savings against warnings of costly mandates for millions of American households. The conversation explores the core legal dispute over what defines an appliance’s “performance,” the real-world costs homeowners might face, the technology behind high-efficiency heating, and the potential ripple effects on our energy grid if gas heating is pushed aside.

The D.C. Circuit Court concluded that how a furnace vents heat does not qualify as a protected “performance characteristic.” Could you explain the legal reasoning behind this distinction and what specific arguments the gas industry is now presenting to the Supreme Court to overturn it?

The D.C. Circuit’s decision really boiled down to a narrow interpretation of the law. The court viewed the primary “performance” of a furnace as heating a home to a certain temperature. From their perspective, the method of venting waste heat—whether it’s hot exhaust up a traditional chimney or acidic condensate out a plastic pipe—is a design feature, not a core function protected by the Energy Policy and Conservation Act. However, the gas industry is now arguing to the Supreme Court that this view is not only “legal error” but also “practical folly.” Their core argument is that compatibility with existing infrastructure is a critical performance characteristic. They contend that non-condensing furnaces are designed specifically to work with the standard chimneys and natural-draft venting systems already built into millions of American homes, and by mandating a technology that cannot use this infrastructure, the DOE is unlawfully eliminating an entire product class that consumers need.

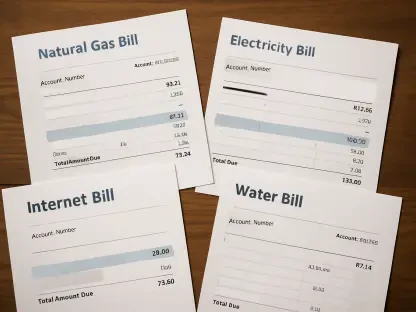

With non-condensing furnaces representing over half the U.S. market, what are the specific, step-by-step challenges and renovation costs a homeowner might face when replacing one with a condensing unit? Please describe the practical implications for different types of homes.

This is where the policy hits the pavement, and it can get complicated and costly very quickly. A traditional non-condensing furnace, which is about 80% efficient, vents hot exhaust up a metal or masonry chimney. A new condensing unit, which tops 90% efficiency, extracts so much heat that the exhaust is cool and creates an acidic condensate. This means you can’t use the old chimney. Instead, a contractor has to run new PVC plastic pipes, often horizontally through the side of the house, for both intake and exhaust. In a home with an unfinished basement and easy access to an exterior wall, this might be a manageable, though still additional, cost. But imagine an apartment in a multi-story building, or a historic home with plaster walls. The renovations could involve extensive drywall work, running pipes through finished living spaces, and finding a suitable place to drain the condensate, turning a simple appliance swap into a significant remodeling project. This is the financial burden the gas industry warns will saddle families.

Efficiency advocates claim these new standards rely on proven technologies that save consumers money. From a technical standpoint, how do condensing furnaces achieve their 90%-plus efficiency, and what evidence supports the claim that these savings offset the initial installation and retrofitting costs for families?

The technology itself is quite clever and has been around for a while. A standard furnace burns gas and sends the hot exhaust, including water vapor, straight up the chimney—wasting a lot of heat in the process. A condensing furnace has a second heat exchanger that captures that excess heat from the exhaust vapor. It cools the vapor down until it condenses back into liquid water, releasing a significant amount of latent heat that is then used to warm the home’s air. This is how it jumps from roughly 80% efficiency to 90% or more. The argument from advocates, like the Appliance Standards Awareness Project, is that this is a proven, off-the-shelf technology. They contend that by forcing the market to adopt this more efficient standard, families are protected from being locked into higher energy bills for the 15-to-20-year lifespan of a new, less efficient furnace. The long-term fuel savings, they argue, will more than pay for the higher upfront cost of the unit and any necessary retrofitting over the life of the appliance.

The gas industry argues that these regulations could force homeowners to abandon gas heating entirely and switch to electric. What are the potential impacts on the electrical grid and on consumer utility costs if millions ofhouseholds were to make this switch in a short timeframe?

This is the billion-dollar question for the utility sector. The gas industry’s “doomsday” scenario is that if the renovation costs for a new condensing gas furnace become too high, homeowners will be forced to switch to all-electric heating. While modern electric heat pumps are very efficient, a massive, uncoordinated switch from gas to electric for home heating would place an enormous strain on the electrical grid, especially during peak winter demand. Most local distribution systems are not built to handle that kind of load increase. This could necessitate massive, costly infrastructure upgrades—new substations, larger transformers, and upgraded power lines—the costs of which would ultimately be passed down to all electricity customers, not just the ones who switched. It raises serious concerns about grid reliability during extreme cold snaps and could lead to significantly higher utility bills for everyone as the entire system strains to meet the new demand.

What is your forecast for the Supreme Court’s decision on this case and its long-term impact on federal energy efficiency standards for other home appliances?

This is a tough one to predict, as it hinges on whether the Court takes a narrow, technical view of the statute or a broader, more practical one. If the justices focus strictly on the text, they might agree with the D.C. Circuit that venting is a design choice, not a protected performance characteristic. However, if they are persuaded by the “practical folly” argument—that a rule is effectively a ban if it makes a product unusable for a huge portion of its intended market—they could side with the gas industry. A ruling in favor of the DOE would embolden federal agencies to push for stricter efficiency standards across a range of appliances, accelerating the transition away from fossil fuels. Conversely, a ruling for the gas industry would be a major setback for the energy efficiency movement. It would establish a precedent that an appliance’s ability to integrate with existing home infrastructure is a protected feature, potentially shielding other legacy technologies from being regulated out of the market and forcing regulators to take a much more cautious and incremental approach to future standards.