The explosive proliferation of data centers across the country has ignited a contentious debate, often casting these massive energy consumers as an existential threat to grid stability and customer affordability. This binary perspective, which pits economic development against the integrity of the electrical system, fails to capture the full picture and overlooks a more nuanced, strategic path forward. While the challenge of integrating these multi-megawatt facilities is undeniable, a proactive and data-driven approach to rate design and contractual agreements can transform data centers from a perceived liability into a valuable, flexible grid asset. By moving beyond outdated perceptions and embracing innovative solutions, utilities can ensure these new, large customers not only pay their fair share of infrastructure costs but also actively contribute to a more reliable and efficient power system for all. This shift in perspective is not merely optimistic; it is essential for navigating the energy demands of our increasingly digital world.

The Data Center Paradox: Inflexible Beast or Flexible Partner?

Debunking Old Myths

The prevailing narrative often characterizes data centers as unyielding, monolithic consumers of power, demanding an unwavering energy supply 24/7 without offering any operational give-and-take. This image, largely a relic of the industry’s state a decade ago, portrays a brute-force load that relentlessly strains grid resources. While this characterization may have once held some truth, it is now an obsolete simplification that fails to acknowledge the profound operational sophistication and inherent adaptability of modern hyperscale facilities. These are not just passive consumers; they are highly advanced operations with significant, albeit often untapped, sources of flexibility. Their energy consumption patterns, driven by predictable computational cycles, are far more stable than most other large commercial or industrial loads. This outdated view not only misrepresents the capabilities of modern data centers but also hinders the development of creative solutions that could benefit the entire electrical ecosystem.

The reality of today’s advanced data center operations stands in stark contrast to these antiquated myths, revealing a wealth of latent flexibility that can be harnessed for the grid’s benefit. For instance, these facilities maintain remarkably high and predictable load factors, often exceeding 75%, which simplifies forecasting for utilities. A substantial portion of their energy usage is dedicated to modulatable cooling systems, which can be temporarily cycled down or adjusted without compromising core computing functions, offering a significant and immediate source of load reduction. Furthermore, many modern centers are already equipped with substantial on-site backup generation and, increasingly, battery storage systems. These assets, primarily intended for emergencies, can be repurposed as dispatchable grid resources during peak demand events. The most sophisticated global operators even possess the capability to shift computational tasks across a network of data centers in different geographic regions, allowing them to dynamically reduce electrical demand in a specific location experiencing grid stress without disrupting services for end-users.

Pinpointing the Real Challenge

The true concern for utilities and regulators is not the supposed inflexibility of data centers but the substantial financial risk associated with serving them. Integrating a single multi-megawatt facility often requires massive, capital-intensive upgrades to local transmission and distribution infrastructure, investments that can take decades to recover through rates. The primary danger arises if a data center project is significantly delayed, canceled mid-construction, or if the operator ceases operations prematurely. In such scenarios, the utility is left with highly specialized, non-transferable infrastructure—so-called “stranded assets”—whose costs must be recovered. If the responsible party is no longer present, this financial burden is unfairly shifted to the existing residential and commercial customer base, leading to higher bills for everyone else to cover infrastructure they do not directly use. This issue of cost recovery, not operational rigidity, is the central problem that must be addressed to ensure equitable outcomes for all stakeholders.

This financial exposure creates a significant dilemma for utility planners and state regulators, who are tasked with maintaining both grid reliability and customer affordability. The scale of investment required to connect a single hyperscale data center can rival the cost of upgrading infrastructure for an entire town. Without proper safeguards, approving such a project becomes a high-stakes gamble with the public’s money. A sudden change in a data center operator’s business strategy, a corporate merger, or a shift to a more favorable market could leave a community with a billion-dollar extension cord to nowhere. This potential for stranded costs forces utilities to be extremely cautious, sometimes leading to a perception that they are anti-development. However, their hesitation is rooted in a fiduciary duty to protect their existing ratepayers from subsidizing the business risks of a single, large commercial entity. Therefore, the core challenge is to develop frameworks that isolate this financial risk, ensuring the party that necessitates the investment is also the party that guarantees its full recovery.

Forging a New, Symbiotic Relationship

Securing the Foundation with Smart Contracts

The foundational solution to mitigating this immense financial risk lies in the implementation of robust contractual safeguards that ensure data centers bear the full cost of the infrastructure built specifically to serve them. This approach is not punitive but rather an application of basic cost-of-service principles that are standard in many other industries. Utilities are increasingly adopting such measures, as seen with Ameren Missouri’s requirement for long-term contracts that include significant exit fees sufficient to cover any undepreciated infrastructure costs should the data center cease operations prematurely. Similarly, AEP Ohio’s data center tariff mandates that operators either meet a minimum investment-grade credit rating or provide substantial financial collateral. These mechanisms guarantee that the utility can recover its investment even if the customer defaults, effectively insulating the general body of ratepayers from the business risks associated with a single large user and creating a fair and stable financial environment.

Far from being a deterrent, these clear and binding contractual arrangements are often welcomed by the most sophisticated data center operators. For these large corporations, such agreements provide the long-term cost certainty and operational stability that are essential for their own multi-billion-dollar capital planning and investment decisions. The process of securing financial collateral or agreeing to a long-term contract with defined exit clauses aligns with standard commercial practices they engage in for other critical aspects of their business. It removes ambiguity from the utility relationship and establishes clear expectations from the outset. This mutual understanding and financial de-risking create a solid, predictable foundation. Once this bedrock of financial security is in place, the relationship can evolve beyond simple risk mitigation and into a more dynamic and mutually beneficial partnership focused on unlocking operational value for both the data center and the broader electrical grid.

Incentivizing Partnership Through Innovative Rates

With the foundational financial risks addressed through robust contracts, utilities can shift their focus from protection to partnership by designing innovative tariffs that actively incentivize data centers to leverage their inherent flexibility for the grid’s benefit. By moving away from traditional flat or simple time-of-use rates, utilities can implement more dynamic mechanisms like real-time pricing and critical peak pricing. These rates expose data centers to the actual, fluctuating cost of energy, providing powerful economic signals that motivate operators to shift non-critical, energy-intensive computing tasks to off-peak hours when power is cheaper and more abundant. During moments of extreme grid stress, such as a heatwave, a critical peak price can provide a compelling incentive to drastically reduce consumption, thereby helping to maintain system stability and avoid more drastic measures like rolling blackouts, all while allowing the operator to achieve significant cost savings.

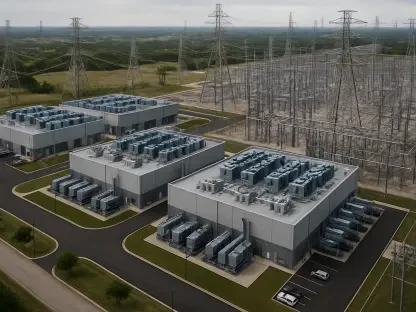

This collaborative relationship can be taken a step further through the development of programs that formalize the data center’s role as a grid asset, effectively treating it as a Virtual Power Plant (VPP). In this advanced model, utilities create frameworks to compensate the data center for deploying its on-site resources—such as backup generators or battery storage systems—to actively support the grid during periods of high demand or emergency conditions. Initiatives pioneered by utilities like Duke Energy exemplify this approach, allowing a data center to earn a new revenue stream by contributing its capacity. In return, the utility gains a valuable, dispatchable resource that enhances system-wide reliability and helps defer or avoid the need to build expensive new peaking power plants. This transforms the data center from a passive load to be managed into an active participant that contributes to a cleaner, more efficient, and more resilient energy future for the entire community.

The Utility’s Call to Action

Successfully implementing these sophisticated contractual and rate structures demanded a fundamental evolution in utility capabilities, moving beyond the traditional systems of the past. To forge these new partnerships, utilities invested in modern strategic tools and processes. This transformation began with the adoption of advanced analytics and modeling platforms, which allowed them to rapidly simulate the system-wide impacts of complex new tariffs and analyze customer data to understand potential revenue shifts. This ensured equitable outcomes could be designed and verified long before a formal rate case was filed. The modernization of legacy billing systems was also essential, as older platforms could not handle the intricate, real-time calculations required for dynamic pricing, multi-layered demand charges, and VPP compensation. These investments were critical for the accurate and automated implementation of the new, flexible frameworks that underpinned this symbiotic relationship. This strategic shift required a new mindset, viewing technology not as a back-office cost center but as a strategic enabler of a more dynamic and resilient grid.