During a particularly challenging summer, Iowa City confronted a pressing environmental issue as nitrate levels in the Iowa River soared to alarming heights, raising concerns about the safety of the local water supply and its impact on thousands of residents. Heavy rainfall, coupled with agricultural runoff, pushed nitrate concentrations well beyond the safe drinking water standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), posing potential health risks. Despite these daunting circumstances, the city demonstrated remarkable resilience, maintaining water quality without resorting to the restrictive measures seen in nearby Des Moines. This success story sheds light on the intricate balance of environmental factors, strategic water treatment methods, and municipal planning that allowed Iowa City to navigate a crisis that could have disrupted daily life. By delving into the specifics of this situation, a clearer picture emerges of how local conditions and proactive management can make a significant difference in addressing widespread water quality challenges across Iowa.

Unpacking the Nitrate Crisis

The issue of nitrate contamination in Iowa’s waterways is a persistent seasonal struggle, particularly intensified during the summer months when runoff from agricultural fields and urban landscapes surges into rivers. This year, the Iowa River recorded a staggering peak of 17.2 mg/L in May, far exceeding the EPA’s safe limit of 10 mg/L for drinking water. Such elevated levels are not merely numbers on a chart; they carry serious health implications, including risks of thyroid dysfunction and certain types of cancer, affecting the well-being of hundreds of thousands who depend on these water sources. The urgency to manage nitrate levels is thus not just an environmental concern but a critical public health mandate, requiring robust systems to ensure that what flows from taps remains safe for consumption. This recurring problem underscores the need for consistent monitoring and innovative solutions to mitigate the impact of natural and human-induced factors on water quality.

Another layer to this challenge is the role of extreme weather patterns, which this summer amplified the nitrate issue in unexpected ways. With rainfall totals hitting 9.20 inches in July—over 5 inches above the historical average—the region experienced one of its wettest periods on record. While this deluge reduced the demand for manual irrigation on farmland, potentially curbing some nitrate runoff, it also led to widespread flooding that inundated groundwater channels with contaminated water. According to local water officials, these opposing effects often cancel each other out, maintaining a delicate status quo in nitrate management. The complexity of predicting how precipitation influences contamination levels highlights the unpredictable nature of environmental challenges and the importance of adaptive strategies in water treatment. This dynamic illustrates why cities like Iowa City must remain vigilant and flexible in their approach to safeguarding water resources amidst fluctuating natural conditions.

Strategic Water Management in Action

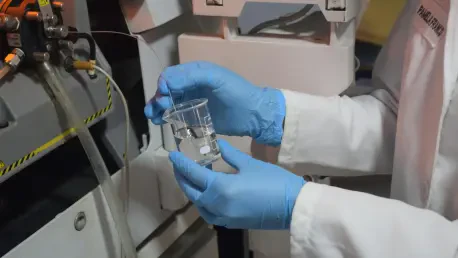

One of the key reasons Iowa City avoided the water restrictions that plagued Des Moines was the stability in water demand among its residents. Unlike its neighboring city, which grappled with a sharp spike in irrigation needs leading to overwhelmed filtration systems, Iowa City’s customer usage remained relatively steady. This allowed the local water treatment facilities to focus on managing elevated nitrate levels without the added pressure of excessive demand. Water Superintendent Jonathan Durst noted that the city relied heavily on dilution, a process of blending nitrate-laden river water with cleaner groundwater sourced from four major Midwest aquifers, including the Dakota and Silurian-Devonian. This method effectively kept nitrate concentrations below the EPA’s threshold without incurring additional costs, thanks to pre-existing infrastructure. Such an approach demonstrates how foresight in resource management can prevent crises from escalating into public inconveniences.

Beyond demand stability, the choice of treatment methods played a pivotal role in Iowa City’s ability to handle the nitrate surge. Among the options considered—distillation, filtration, and dilution—distillation was quickly ruled out due to its prohibitive cost for large-scale municipal use. Instead, the city prioritized filtration and dilution, leveraging its access to abundant groundwater resources to dilute contaminated river water. This practical solution not only maintained water safety standards but also avoided the need for expensive new infrastructure or emergency measures. The effectiveness of this strategy highlights the importance of utilizing local resources tailored to specific environmental challenges. It also serves as a reminder that sustainable water management often depends on adapting proven techniques to current conditions, ensuring that residents continue to have access to safe drinking water without disruption, even during peak contamination periods.

Regional Contrasts and Long-Term Challenges

A striking contrast emerges when comparing Iowa City’s response to that of Des Moines, where high irrigation demands necessitated a temporary ban on lawn watering in June, only lifted by late July after filtration capacity improved. Iowa City’s ability to sidestep such restrictive measures can be attributed to its manageable water usage patterns and strategic reliance on dilution with groundwater. This disparity reveals how localized factors, such as consumer behavior and infrastructure readiness, can significantly influence municipal responses to environmental crises. While Des Moines struggled under the weight of demand outpacing treatment capabilities, Iowa City’s steady approach prevented similar public disruptions. This comparison underscores the value of tailored water management plans that account for unique regional dynamics, offering insights into how other cities might prepare for similar challenges by balancing demand and resource availability.

Looking beyond immediate responses, the sources of nitrate contamination and potential future risks paint a broader picture of concern for Iowa’s water quality. Agriculture stands as the dominant contributor to nitrate runoff, with urban stormwater from roads and parking lots adding to the problem. Although municipal facilities, including Iowa City’s wastewater treatment plant, effectively manage downstream pollutants, the upstream challenges tied to farming practices remain largely unaddressed. Water officials have expressed apprehension about scenarios where even dilution may fall short if nitrate levels continue to climb or groundwater resources diminish over time. This looming uncertainty calls for comprehensive strategies that tackle contamination at its source, rather than relying solely on treatment solutions. Addressing these root causes will be essential to ensuring long-term water safety across the state, pushing for collaborative efforts between municipalities, farmers, and policymakers.

Reflecting on Sustainable Solutions

Reflecting on the events of this past summer, Iowa City’s adept handling of elevated nitrate levels through stable demand management and dilution strategies stands as a testament to effective municipal planning. The city’s ability to avoid the restrictive measures seen elsewhere, despite facing similar environmental pressures, provided a sense of normalcy for residents during a challenging period. However, the persistent influence of agricultural runoff and unpredictable weather patterns served as stark reminders of the fragility of current systems. Moving forward, the focus must shift toward sustainable interventions that address contamination upstream, such as improved farming practices and enhanced stormwater management. Collaborative initiatives involving local authorities, agricultural stakeholders, and environmental experts could pave the way for innovative policies that reduce nitrate input into waterways. By prioritizing prevention alongside treatment, Iowa City and similar communities can build a more resilient framework for water quality, ensuring safer resources for future generations.